New Zealand is one of the most Food Secure nations in the world, and is a major food exporter. With major trading partners the world over, and an economy dependent on this revenue to pay for imports of other goods, New Zealand is a perfect case study for export fleet requirements without the need to balance for food imports. With a small population and the ability to diversify the economy to produce the majority of domestic needs as shipping becomes increasingly expensive and difficult, New Zealand will still need to export large amounts of food, and other countries will likely have to rely on these exports to feed their ever more urbanized populations.

New Zealand’s government has acknowledged the challenges of freight dependent agricultural economies in its December 2020 edition of Situation and Outlook for Primary Industries, stating “Over 99 percent of New Zealand’s primary sector exports by volume are exported by sea… averaging 2,920 thousand tonnes each month. … On a volume basis, around 75 percent of New Zealand’s exports by sea are forestry products, with dairy and horticulture the next two biggest sectors.” (Ministry for Primary Industries. Situation and Outlook for Primary Industries, December 2020 Wellington, NZ: Ministry for Primary Industries, 2020)

Only about 0.2 percent of New Zealand’s exports are by air, and are mostly highly perishable commodities which are unlikely to be viable for long-distance exportation in a Sail Freight future. Businesses have adapted to this situation by changing their approaches and products to longer shelf lives, and looking for a more diversified shipping base. (Ministry for Primary Industries. Situation and Outlook for Primary Industries, December 2020 Pp 14)

Sail Freight Tonnage Needed

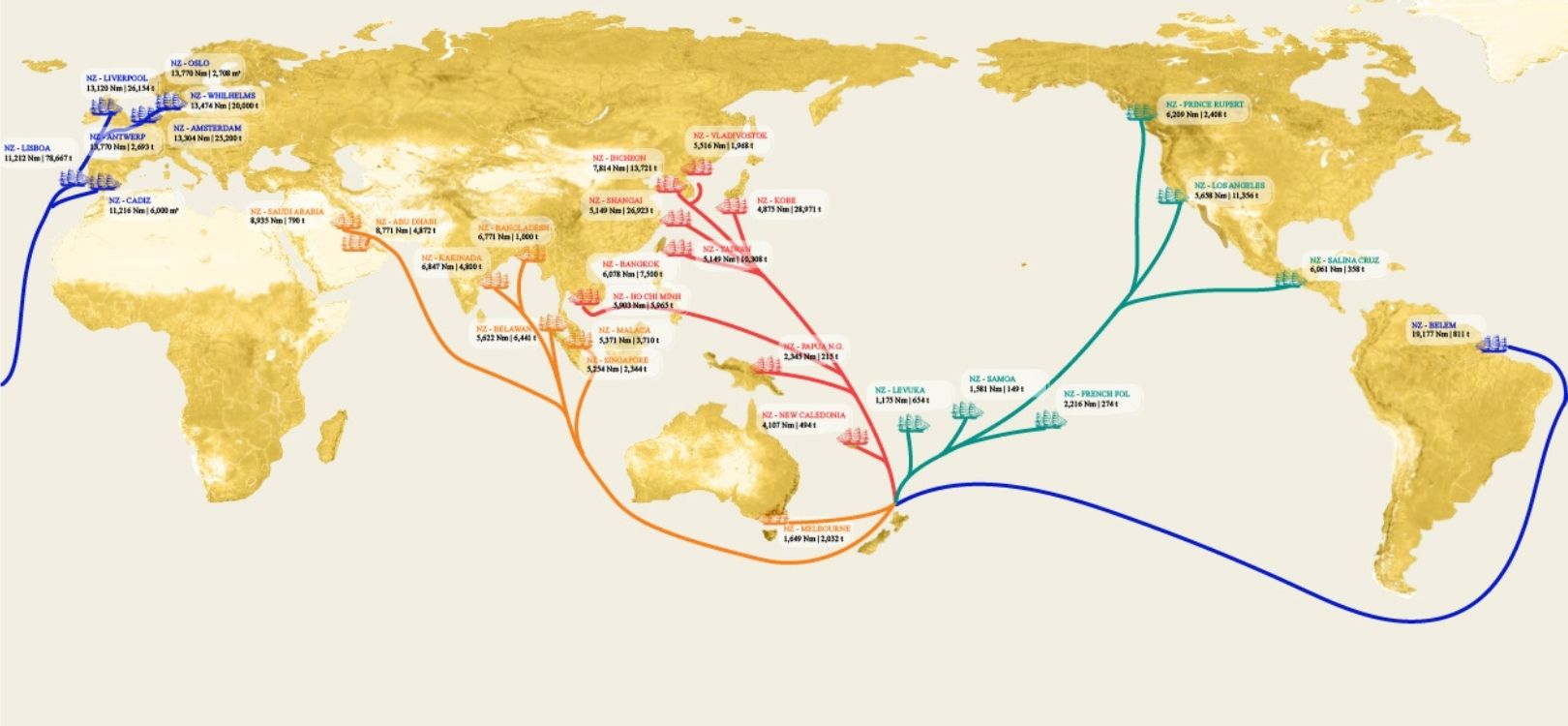

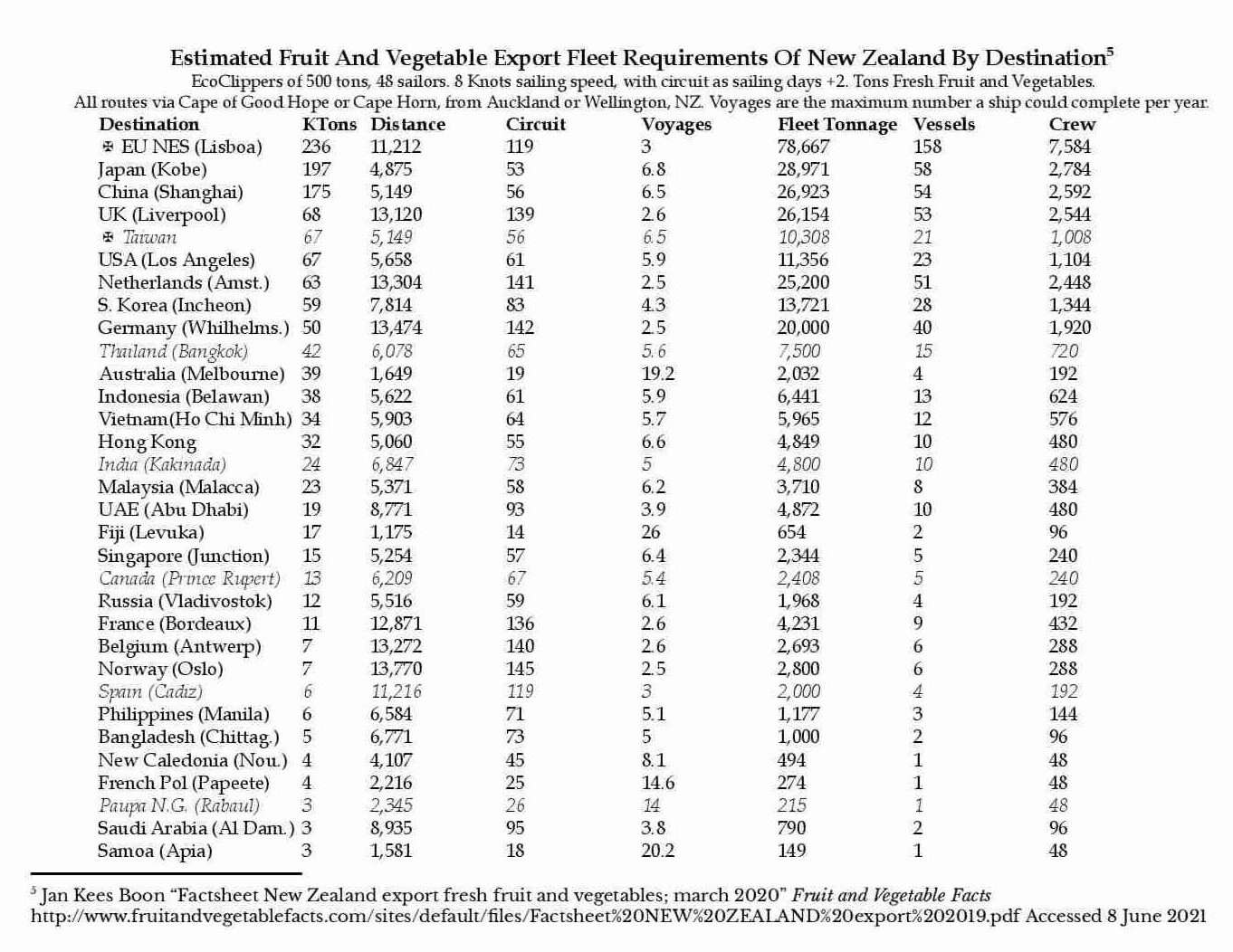

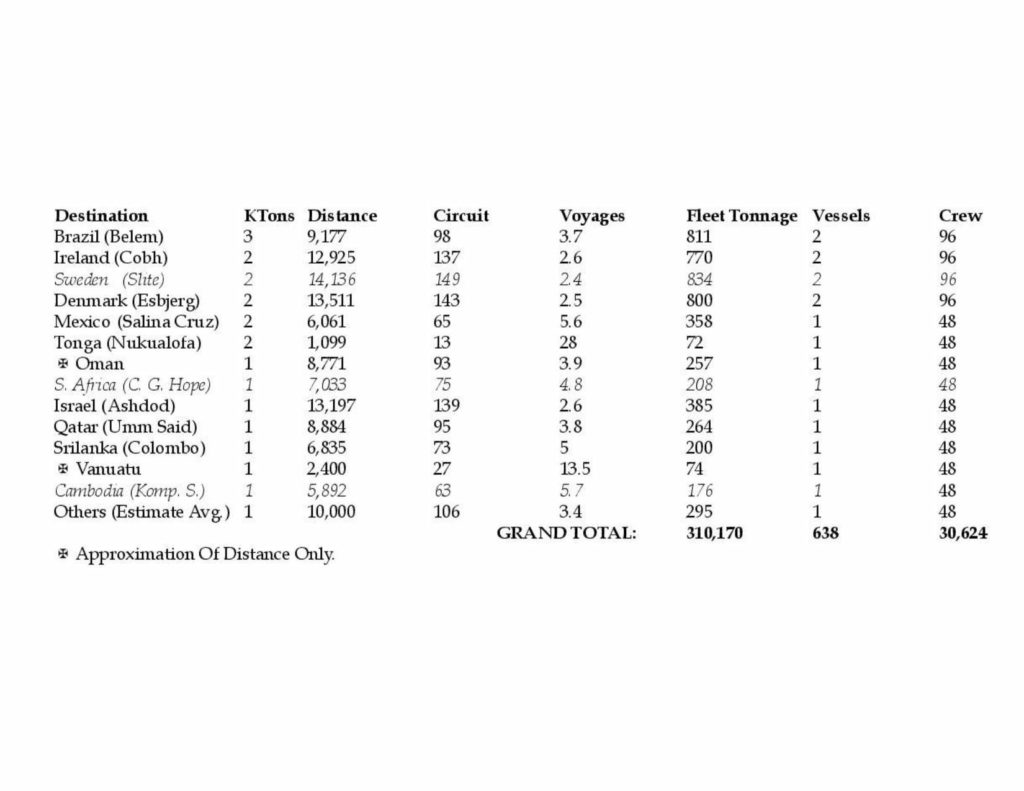

Sail Freight would be an ideal situation for New Zealand, as it imports a large proportion of its oil, and thus as prices for shipping fuels rise it will benefit from reducing its use of maritime fuels which would cut into the trade balance brought home by exports. However, the voyage to various locations can be long and challenging. For the sake of this exercise, we will create fleets for two major export classes: Wood Products and Fruit and Vegetables. The use of 500 ton EcoClippers with 500 cubic meters of storage space will be the standard, with 48 crew sailing an average speed of 8 knots (Sailvolution and EcoClipper B.V. “EcoClipper500 Short Specifications” Alkmaar, Netherlands: EcoClipper B.V., 2020). This article will cover Fruits and Vegetables, with a future article covering forestry products.

There is some nuance worth noting in this model. With only 20 crew, 8 of whom are trainees, the EcoClipper can carry its full 500 tons of cargo, up to 690 cubic meters. This is reduced to some 420 cubic meters when the full complement of trainees is on board. Here we use the larger crew and smaller cargo for a least-efficient-case scenario. The figure of 500 tons and 500 cubic meters is used in these blogs as an approximate average. While the speed of 8 knots average over the course of a voyage may be high compared to historical averages, it is used to retain comparability in fleet tonnages per capita to Woods’ Master’s thesis on the adoption of sail freight at scale (Woods, Steven. “Sail Freight Revival: Methods of calculating fleet, labor, and cargo needs for supplying cities by sail.” Master’s Thesis. Prescott College, 2021). The actual speed achieved by an EcoClipper is likely to be between 4-5 knots over the course of a voyage, but the actual speeds attained can only be calculated accurately when the ship is in operation. Fleet tonnages can be doubled to bring the model to a 4 knot average speed.

Challenges

With this information in hand, there are a few immediately obvious concerns, the first of which is the duration of voyages to the highest-volume trade partners. With a one-way voyage of some 60 to 70 days not uncommon for trade to the EU, and over 30 days in most cases, there are challenges to preserving fruit’s freshness. The additional energy, space, and tonnage associated with icing or refrigerating the cargo over such an extended period will undoubtedly increase the fleet tonnage required, especially as the main fruits exported by New Zealand would need to be kept at low temperatures to prevent spoilage. These include Kiwifruit, which accounts for 55% of New Zealand’s fruit and vegetable export earnings, as well as apples, pears, avocados, and cherries (Ministry for Primary Industries. Situation and Outlook for Primary Industries, December 2020 Pp 23-25). Exports of Wine will not be nearly as effected by lack of refrigeration when compared to fresh fruits, but wine makes up far less of New Zealand’s exports.

This predicts two changes which must be made in New Zealand’s export economy: More processing must be completed before export, and a shift to more export-friendly crops is likely to occur. These will most likely include an increase in grains, legumes, and pulses, while fruit exports begin to take the form of canned, dried, candied, concentrated, fermented, distilled, or processed fruits. A move to frozen fruits incurs the same refrigeration problems as fresh fruit, but requires more energy to maintain lower temperatures.

The second concern is labor. It would require 0.37% of New Zealand’s population to crew only the fruit and vegetable fleet. While foreign-flagged vessels may take up some of the strain on New Zealand’s behalf due to their own dependence on imported foods, there will still be a significant draw on economic resources to support the fleet.

The third concern is the likelihood of multi-legged trade reducing the effective fleet tonnage of vessels. This model is based on a bilateral arrangement of trade, and additional legs immediately increases fleet requirements.

Other New Zealand Fleets

New Zealand also exports Seafood, Lumber, Grains, Meat, and Wool in large volumes. Meat and seafood, like fruits and vegetables, would require cooling, or pre-export processing such as canning, drying, or salting. These commodities will each need their own fleet calculations, and since lumber makes up some 75% of the country’s exports by volume, these combined fleets are likely to be quite large. Supplying the necessary ships and crews could be taxing if New Zealand had to do so all on its own, and could not rely on foreign-flagged shipping to take up some of the burden. An examination of the Lumber Fleet is worthwhile, and requires a bit of a different approach than food; cargo capacity needs to be measured in cubic meters, instead of tons.

With this set of challenges facing New Zealand in a transition to a zero-emissions shipping environment, there will undoubtedly be changes in the export regime. What exactly those changes will be is yet to be determined, but it is likely to result in a significant change in the way fruits and vegetables are processed domestically before export.

Steven Woods has worked in Museums and Historic Sites for over 20 years. He holds 4 college degrees, including a BA in History from the Jesuits at LeMoyne College, and a Master’s Degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities from Prescott College. His Master’s Thesis was on supplying the New York Metro Area with food by Sail Freight.