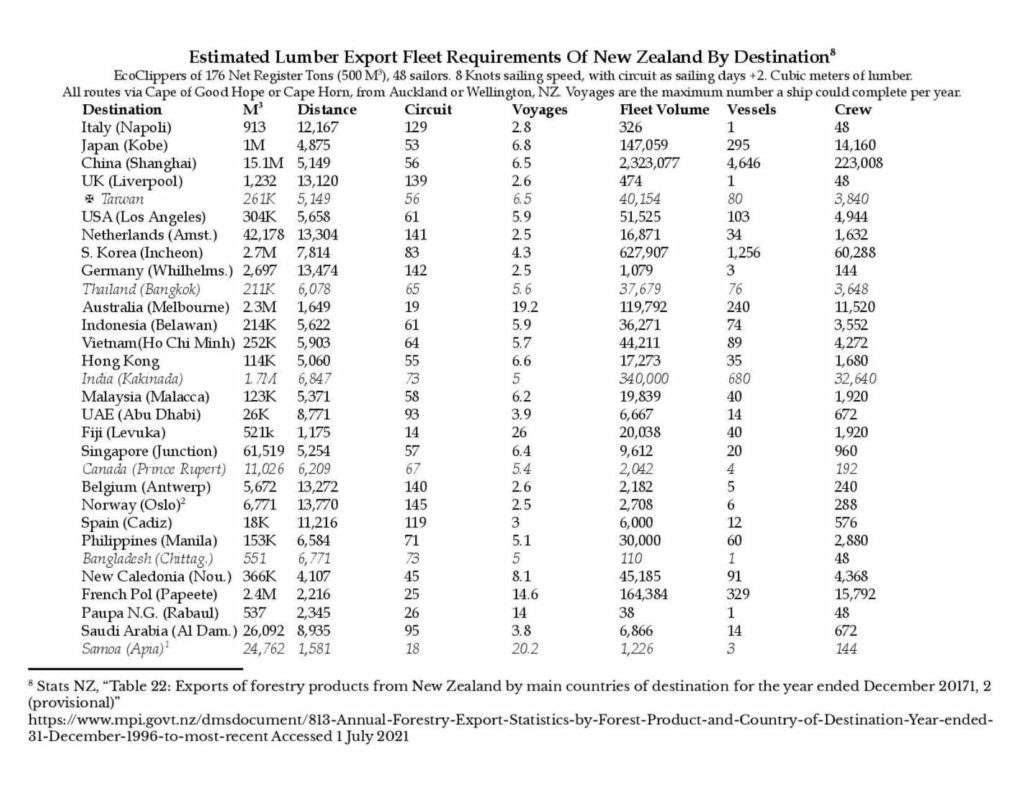

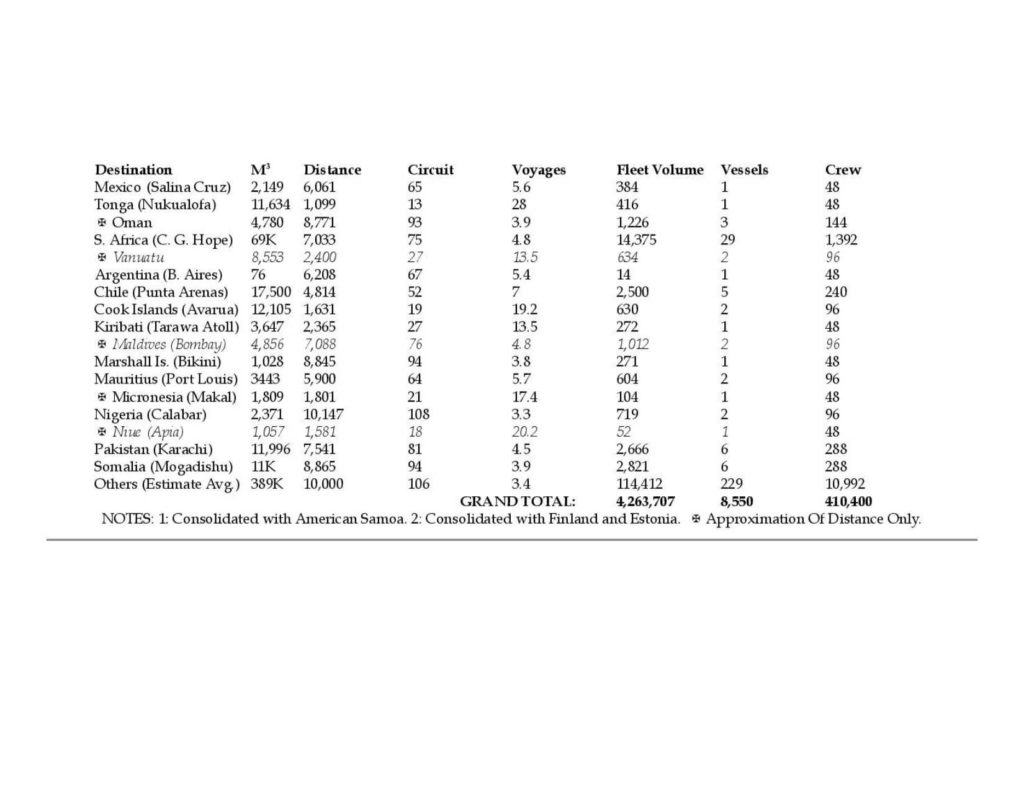

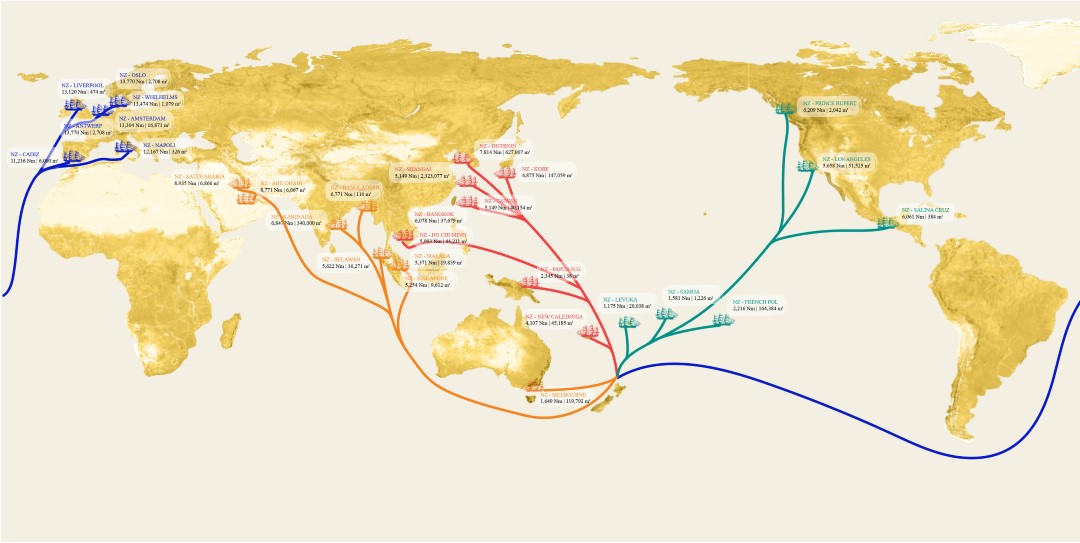

As explained in Part One of this series, New Zealand is a major exporter of food and timber. With the basic rules of calculating fleet requirements covered there, we can move quite directly into the largest export by volume from New Zealand: Forestry Products.

Method of Calculating The Timber Fleet

In the data used to calculate the table below, wood pulp and paper were given in tons, which was converted to cubic meters. This was done using the density of paper at about 1.2 tons per cubic meter. Thereafter, all the types of wood products were aggregated into a single figure for volume destined to each port.

With wood’s density being less than one ton per cubic meter, and wood pulp, paper, and paperboard being a relatively small amount of the cargo for most ports overall, it seems safe to assume the cargoes will not be dense enough to overwhelm the ship’s cargo deadweight tonnage when measured by volume instead of mass.

The table gives a decent idea of the amount of shipping needed for this trade. With the majority of export volume from New Zealand being forestry products as aforementioned, this fleet should give the closest indication of a needed fleet tonnage. For a margin of safety, simply doubling this as New Zealand’s fleet may be a wise move, to account for idle time and other delays.

The Importance of Larger Ships

Using a larger ship than an EcoClipper500, with for example 4000 Cubic Meters of hold capacity will be a far more efficient way to transport cargoes such as lumber. With front hatches like traditional wood schooners, loading of wood products would be far easier. For example, the vessel and crew requirements for the China trade in Lumber drops from 4,646 ships and over 223,000 crew using EcoClippers, to only 581 ships and a little less than 28,000 crew by using a vessel with 4000 cubic meters of cargo capacity and a crew of 48. For bulky cargoes such as wood this becomes especially important, as they are generally not high-value items, and must be moved in large volumes to be economical cargo.

Small Ports and Small Ships

Small vessels can take over some trade routes entirely: When looking back at the Fruit and Vegetable table as well, Papua New Guinea needs a combined fleet tonnage and volume of only 253. This makes it prime territory for a single EcoClipper500 to ply the route with a half-empty cargo hold to allow for goods not accounted under Lumber and Fruits.

As this is only a 26 day circuit and it could be done repeatedly through the year, this EcoClipper could also use its additional cargo space to make less frequent trips with more time in each port.

This could be a mutually beneficial arrangement for both New Zealand and the importing nation, as an EcoClipper employed in such a bilateral trade arrangement would reduce fuel demands and costs in both countries, which are likely to be net petroleum importers. The hiring of crew and trainees principally from these two locations starts the process of building both nations’ domestic windjammer labor pool. Provided this training is reasonably priced and jobs decently paid after training, the sailors graduating the EcoClipper programs will be able to accelerate the adoption of both domestic and international sail freight in their regions, further reducing fuel import cost burdens and carbon emissions.

Domestic Movement by Sail Freight

New Zealand will also be in need of a domestic fleet for the movement of agricultural goods between islands, and along the country’s many miles of coastline. The country is ideally suited to the adoption of Sail Freight due to consistent winds, navigable waters, and the production of crops which are easily moved by sail.

However, this fleet requirement will be small, and likely well within the capabilities of the population to handle without problematic economic impacts. If anything, with New Zealand being an oil import dependent nation at the moment, sail freight will be an economic boon through the retention of income otherwise lost to fuel bills.

Caveats

The obvious caveat to this set of calculations is that exports will not always use a domestic fleet, and thus can only be considered as a model for overall capacity. The principal of calculation can be used effectively, and shows a need for a very large amount of shipping, especially among Island States, but all of this need not be provided by New Zealand alone. While the specific means and routes of climate adaptation which may be taken by states such as New Zealand may be very different from their current economy, their need for shipping capacity is unlikely to disappear over the coming decades.