The compass is a remarkable instrument. Not only is it one of the oldest and most fundamental navigational tools on-board a ship, but our relationship we have with the compass as humans is deeply engrained in our existence. The symbol of the compass represents our life’s heading, of our morality; consistently pointing us back to the true way of being if we stray from the path.

“Symbols and emblems were everywhere… Everything stood for something else; if you had the right dictionary, you could read Nature itself.”

― Philip Pullman, Northern Lights

In a world of phenomenal technological advances, we unquestionably accept what is presented to us. How many of us pick up our phone and can use a map service with inbuilt compass? It is worth remembering the thousands of years of observation, recording, experiments and the satisfying symbiosis between humans and Earth that has brought us to this place today.

Compasses At Sea

There are various compasses which have been designed and developed for different uses. At sea, these are…

- The gyroscopic compass which points to the true north pole. This electronic compass creates gyroscopic inertia through a spinning wheel, using the combination of forced gravity and daily rotations of the Earth. I would recommend reading the entry in the Encyclopaedia Britannica for a concise description of this fascinating invention: https://www.britannica.com/technology/gyrocompass

- The GPS (Global Positioning System) compass which uses satellite information to find a vessel’s location and is able to plot courses – much like our phone’s map services.

- The magnetic compass which points to the magnetic north pole (the focus of this blog).

Magnetic Fundamentals

“Compass: in navigation or surveying, the primary device for direction-finding on the surface of the Earth.”

– Encyclopaedia Britannica

The Earth acts as a huge bar magnet, which make free-moving magnets align to north and south. However, true north is not the same as the magnetic north. True north relates to north at the top of a map and does not move, whereas magnetic north relates to the huge bar magnet, which moves (slightly) year to year.

Deviation – the error of the magnetic compass due to magnetic disruption on board, and around, a ship. (A few may recall stints at the helm where the compass suddenly spins uncontrollably, creating havoc with the sails, accidental gybes, and alarm amongst the crew as the helmsman dutifully follows the bearing and completes circles. This could be a passing submarine beneath you…)

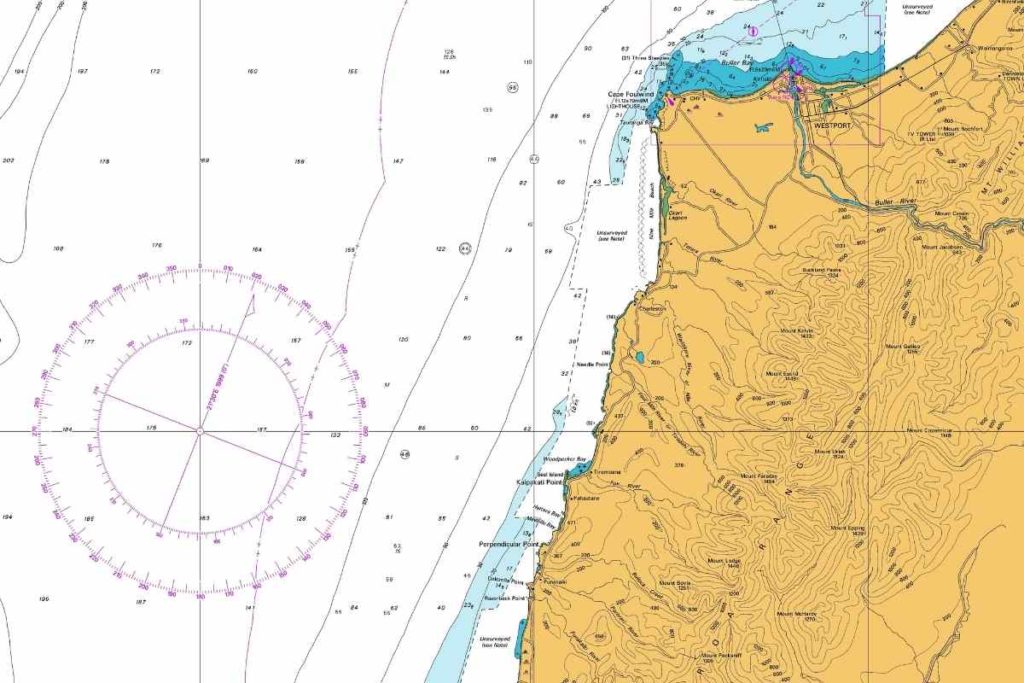

Variation – the angle between true north and geographical North at the position of the observer. This is accounted for with updates to annual charts, or some quick mathematics by the Captain or First Mate, prior to setting off.

History – A Story of Observation

Magnetism has been understood for thousands of years in some form and provides the foundations of magnetic compasses.

“The moment the metal comes near it, it springs towards the magnet, and, as it clasps it, is held fast in the magnet’s embraces… It received its name “magnes,” … from the person who was the first to discover it, upon [Mount] Ida… Magnes, it is said, made this discovery, when, upon taking his herds to pasture, he found that the nails of his shoes and the iron ferrel of his staff adhered to the ground.”

– Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, completed 77 CE

The history of the magnetic compass extends back to antiquity where civilisations used lodestones, pieces of magnetic iron ore, predominantly for geomancy. Whilst lodestones were not used for navigation at this time, people noted that magnetised metals pointed in two directions when moulded and suspended or when drifting in water.

From the 11th or 12th centuries it is believed Chinese scientists developed the magnetic compass for navigation with Western civilisations documenting its use in the 12th century. The development over time included the design of the compass rose, which originally indicated 32 winds, and led to the mounting of a magnetised needle with a protective casing and set in gimbals on a binnacle – a common sight on ships today.

Iron ships

The introduction of iron in shipbuilding presented a problem. In the early 19th century, the deviation of the compass needle due to iron on board ships became obvious.

Iron hulled ships, first developed in the 1870s, caused such a disruption to their compasses, “that it was suggested seriously that such ships would never be successful for they would be quite unsafe in the absence of well-behaved compasses.” (The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea, Peter Kemp)

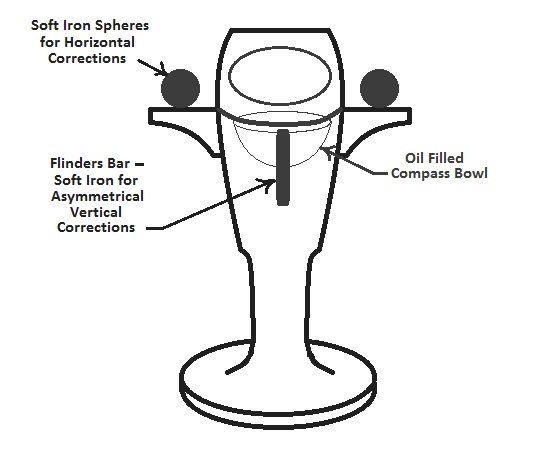

Matthew Flinders, a navigator and explorer, observed that deviation clearly occurred with the presence of the ships iron. He also noted that when ships headed on courses east or west (literally deviating from the Earth’s magnetic rod) deviation occured, then disappeared when bearing north or south. Flinders demonstrated how a ship’s magnetic effect could be neutralised by placing an unmagnetized rod of iron vertically near the compass. This was called the Flinders’ Bar and is still used today.

Further designs were made to reduce the deviation of ships. This included placing magnetised and unmagnetized iron in the vicinity of the compass, a method also used today.

Use on a (steel) EcoClipper ship

Ships are now made of various materials and have access to a myriad of technologies which can plot courses, track movement, speed and automatically updates a ship’s location, all of which are used for navigation. Many of these technologies are onboard for safety and are a requirement in international maritime law.

The EcoClipper500 will have a steel hull and deviation must be taken into consideration when installing the compass. EcoClipper will predominantly use a magnetic compass for helming, with another posted in the Master’s cabin or similar. The ship will also have other electrical navigational tools such as GPS compasses.

This is the beauty of the compass. A physical tool that is so perfectly aligned with the Earth in its design, it can be simply adapted. Yet it is also a symbol that provides consolation that however chaotic the world is around us; we can find a way forward and continue to our destination, wherever that may be.